Marisol, a Venezuelan-American artist who fused Pop Art imagery and folk art in assemblages and sculptures that, together with her mysterious, Garboesque persona, made her one of the most compelling artists on the New York scene in the 1960s, died on Saturday in Manhattan. She was 85.

The cause was pneumonia, Julia M. Ruthizer, her executor, said.

María Sol Escobar, who adopted Marisol as her name when she began exhibiting in New York in the late 1950s, introduced a distinctive new element to the emerging Pop Art lexicon. Influenced equally by pre-Columbian art and the assemblages of Robert Rauschenberg, she began constructing tableaus of carved wooden figures embellished with drawings, fabric and found objects.

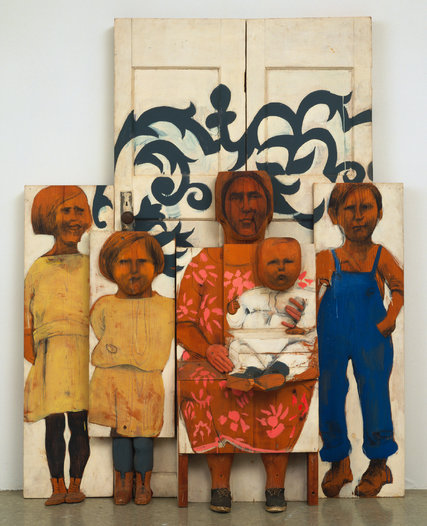

“The Family,” exhibited at the Stable Gallery in 1962, showed a painted-wood family reminiscent of Dorothea Lange’s photographs of the Dust Bowl: a seated mother holding a baby, her three children standing at her side, all staring stiffly at the viewer. They wore real shoes and sneakers. It was a down-market counterpart to her 1960 work “The Kennedy Family,” which made the first family look like a set of tribal totems.

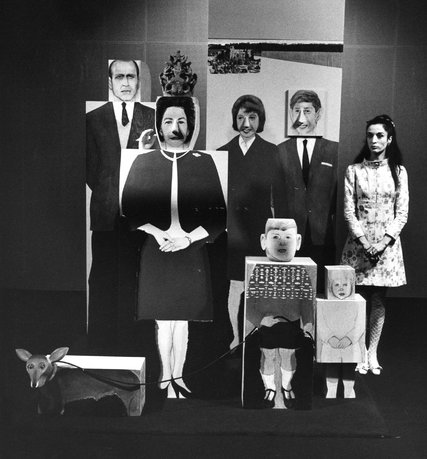

Critics were puzzled. Was Marisol a Pop artist or not? The critic Lucy Lippard, in “Pop Art” (1966), said no, calling her work “a sophisticated and theatrical folk art” that had nothing to do with Pop. It was often overtly political and funny — “clever as the very devil and catty as can be,” John Canaday wrote in The New York Times of her 1967 exhibition featuring sculpture caricatures of the British royal family, President Lyndon B. Johnson and other eminent figures. She drew on celebrity images, as well, creating sculptures of John Wayne and Bob Hope.

Marisol often appeared at parties beside Andy Warhol, who turned the camera on her in his underground films “The Kiss” (1962) and “13 Most Beautiful Women” (1963). She returned the favor by creating a seated Warhol out of wooden boxes and table legs.

As Warhol did, Marisol turned self-absorption into an art form, incorporating casts of her own body parts and images of her face into works like “The Party,” whose 13 figures and two servants all derived from her own features. She also fused commercial products with her work, most notably in “Love” (1962), in which a cast of her own open mouth received an upended Coca-Cola bottle.

Like Warhol and his disciple Jeff Koons, Marisol was aloof and opaque, a master of the gnomic pronouncement. “I don’t think much myself,” she told the critic Brian O’Doherty in The Times in 1964. “When I don’t think, all sorts of things come to me.”

Marisol’s first show at Sidney Janis in 1966 drew the largest crowds in the history of that gallery. She was enormously popular but interviewers found her elusive, and her personal aura nearly eclipsed the art.

The “Marisol legend,” Grace Glueck wrote in The New York Times Magazine in 1965, depended in no small part on “her chic, bones-and-hollows face (elegantly Spanish with a dash of Gypsy) framed by glossy black hair; her mysterious reserve and faraway, whispery voice, toneless as a sleepwalker’s, but appealingly paced by a rich Spanish accent.”

Seemingly indifferent to the public and the demands of an art career, Marisol periodically headed off to remote corners of the globe for years at a time, confounding her dealers.

“She was an incredibly significant sculptor who has been inappropriately written out of history,” said Marina Pacini, the chief curator at the Memphis Brooks Museum of Art, where she organized a traveling survey of Marisol’s work in 2014. “In the 1960s, she had more press and more visibility than Andy Warhol.”

María Sol Escobar was born on May 22, 1930, in Paris, to a wealthy Venezuelan family. Her father, Gustavo, dealt in real estate. Her mother, the former Josefina Hernández, committed suicide when her daughter was 11.

She grew up in Paris and Caracas. After the family moved to Los Angeles in 1946, she attended the Westlake School for Girls and studied art with Howard Warshaw at the Jepson School. She went to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts but left after a year and took courses at the Art Students League of New York, where the naïve, decorative style of Yasuo Kuniyoshi, one of her teachers, was a decisive influence. She also studied with Hans Hofmann at his schools in New York and Provincetown, Mass., but abandoned Abstract Expressionist painting for sculpture after seeing examples of pre-Columbian art at a gallery.

Leo Castelli included her in a group show with Jasper Johns and Rauschenberg in 1957 and that same year presented her first solo show. It could have been an immediate springboard into art-world fame if she had not bolted for Rome, where she lived for two years.

On her return to New York, her shows at the Stable and Sidney Janis galleries tuned her into a star. She was included in “The Art of Assemblage” in 1961 at the Museum of Modern Art, which gave her her own room in the showcase exhibition ”Americans, 1963.” Gloria Steinem profiled her in Glamour. In 1968 she exhibited work at both the Venice Biennale and Documenta in Kassel, West Germany.

She then went on a two-year jaunt around the world. When she returned, the art scene had changed, and she no longer fit in. She turned to more mythic, folk-oriented work, carving mahogany fishes, and explored a more private world in semi-surreal works on paper, filled with violent imagery, bearing titles like “Lick the Tire of My Bicycle” and “I Hate You Creep and Your Fetus.”

In recent years, revisionist critics and curators have rediscovered her work. She was the subject of a retrospective at the Neuberger Museum of Art in Purchase, N.Y., in 2001, and her work was included in two exhibitions in 2010: “Seductive Subversion: Women Pop Artists, 1958-1968,” at the Brooklyn Museum, and “Power Up: Female Pop Art,” at the Kunsthalle in Vienna. Ms. Pacini’s exhibition, “Marisol: Sculptures and Works on Paper,” traveled to El Museo del Barrio in Manhattan.

Marisol, who leaves no immediate survivors, might or might not have cared about the renewed attention. When asked in 1964 how she would like her work to be seen by critics and the public, she seemed puzzled by the question.

“I don’t care what they think,” she said.